family album

As I work on revisions of WHERE THE RIVER IS A ROAD I find myself thinking of the origins of stories. I consider the maps embedded in those narratives. The short memory piece that follows refers back to some of the early collective stories I experienced. It is the visceral sketching out of a house in the cold sand, the rendering of a scary story map, that compels me.

X Marks the Tale

originally published in 2011 F Magazine

Create a square of beach sand. Make it Alaskan. Add gravel, rocks, and ivory yellow grasses bent over and nearly buried in the dust that blows sideways. That is the palette, the printing press of a story that won’t be written but rather spoken in bits and snatches of shrill voices.

I hunch on a slab of embedded driftwood, one of five young girls in a choir of rapt story summoners. My friend, Joanne, squats next to me and wipes her hand over the gritty surface of sand. A breeze, as chill as icicles, tickles the fine hair on the nape of my neck.

Joanne plucks away a bit of twisted wood, then picks out the shard of a broken bottle. After studying the ground for an intent minute, she exhales. She picks up a long thin twig, that points like the ghost of a finger, and begins.

Over choppy water, as gray and blue as old sea glass, gusting air skips and whirls and whips. We face away from the village of Unalakleet, on the western coast of Alaska. Only two places remain in our line of vision: the gravel shore and the churning saltwater. Smells of the village are soaked up in the damp air: wet soil, wool, dog lots, sweat, fish oil, smoke.

The story begins without a word. Lines are scratched into the sand. Scritch, scritch, scritch. Every so often the teller uses the heel of her hand to erase a line. The drawing is that of a house. It is a house with many floors and rooms. There is always an attic.

And, always, there is a basement. No such house exists in Unalakleet, yet the houses in our stories are always drawn from this same foreign blueprint. The textbooks at our school are filled with colors and streets and lawns from another country.

We import the house design and add ghosts of our own.

It is happening all over again, I think. The story is fragmented. Words get lost in the wind. Other words are added by the whispering of air and the crashing of waves. In the basement sits a barrel, like the big cardboard barrels flown in on the Commissary Plane. It resembles the barrels my family packs our worldly possessions into whenever we decide to move someplace new. The barrel in the story is stamped with a white X. Skulls are too difficult to draw in the emery rough sand.

A new family buys the house – foolish people. Without exception the families are large – many children and aunts and uncles. One by one, they are lost. Sooner or later, no matter what element in the story changes, each family member is overcome by curiosity and finds their way into the basement where the lights flicker on and off, on and off, and something scurries in the shadows.

Sooner or later, each person is overcome with the urge to pry off the metal lid and peer inside. None of the story-people can remember owning a barrel with an X on it. Not one of them can resist. They need to know. The lid creaks and groans as it is lifted. Once the barrel is open there is no hope left. Bones and bloody remains pile up in the fated basement while the people upstairs continue to go about their daily business unaware of the danger lurking down below.

How silly and ignorant and happy they seem, without any cause for such hope or such an abundance of happiness. Doomed. Every last one of them. No one is safe. The baby in the crib. Gone. The aana in the rocking chair. Kaput.

The skeleton of the story is so weak it breaks apart like spun sugar. We scream, then giggle. Then we scream again. But behind us lays the dark and silent village. The cemetery, with its tilting crosses and bunches of plastic flowers, huddles next to the town. Pre-dug graves – for whatever misadventures might happen during the long winter when the ground will be too frozen to plunge a shovel into – leave gaping holes for the unwary. It is said that if you fall in one of those holes . . . well that is very bad luck.

My friend pulls her calico wrap around her, a row of safety pins hold it together. A row of safety pins hold our ghost story together. Pop. Pop. I can almost hear them popping open and jabbing us. Ouch. The sole survivor in the story starts down the stairs. We yell at her, “Go back! Run away!”

Then snap the lights come on and, finally, she sees where everyone has been all this time. She runs screaming from the house where someone has once again tacked up a sign: House for Sale.

Picture the cold beach arcing under low clouds. Imagine five girls rocketing across the tundra. Notice the small hillocks and lumps under the pillow soft land. Low brush and fragrant Labrador Tea shrubs are nearly ripped out by a sudden gust. Each rounded hump of earth quivers, each mound is the perfect hiding place for a cardboard barrel, marked with a bone white X.

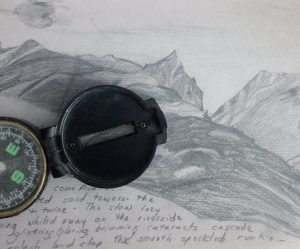

journal entry

Maps in stories can be as ephemeral as a quick sketch with a bullet in the dirt (WHERE THE RIVER IS A ROAD). Or maps can carry the weight of history and the exigency of danger. The silk evasion map from World War II, given to Kiana in TAPPING LIGHT, was more than a scrap of history – it became a talisman.

Such is the heft and import of maps. Maps require care and a kind of patience. Charts on a boat should be rolled tightly and kept in order. Deciphering an atlas one must read between the lines. Who drew the map and why?

And then there are the simpler, more immediate maps. These personal orientations to the lay of the land – the scope of the story and the mind-set of the maker are the most compelling maps to me.

Fragments and old maps from the past inspire new stories and add details to a narrative in which not everything is as it seems. Places I have lived kindle this need to convey the lay of the land. Writing about the fictional town of Fireweed Crossing, as I revise WHERE THE RIVER IS A ROAD, I draw on memories of rivers I have known: the Yentna, the Kobuk, the Kuskokwim.

Attached to these vivid memories is a kind of sensory index which makes possible the creation of a river on paper that indeed sounds, smells and gleams like a river that one can walk beside – a place where one can pause and skip smooth flat rocks across the bend where the ripples have stilled.

I like the imagery in that last paragraph. A perfect toss … a glassy surface .. the curved trajectory of the imperfect stone. The skips beginning long and becoming shorter until the rock slides to a stop and sinks into the river. The ripples of memory and imagination emanating from each skip. I have chains of memories attached to many of the same places your stories are anchored – Unalakleet, Galena, Huslia, Anvik, Rocky Point, the coast near Nome. Thanks for the blog! It’ll be fun to read “The River”.

Thank you, Terry! There are so many vivid stories inspired by rivers.